RP3: Latin America (Andes)

Bones, Skulls and Mummified Ancestors: Human Remains Between Destruction and Veneration in the Andes (16th and 17th Centuries)

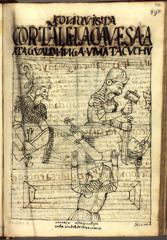

Regional Project 3 explores the tensions between the destruction and veneration of human remains in the Andes. The supposedly first encounter between Incas and Spaniards culminated in the capture and eventual execution of the last Inca king, Atahualpa (Fig. 1). In order to save his body from being burned at the stake, Atahualpa had himself baptised shortly before his execution. The outcome of this encounter not only set the tone for the years that followed, but also represented a process of negotiation regarding Christian and Inca ideas about and on the body.

The Incas, like many cultures in the Andes, practised preserving and mummifying their ancestors and rulers. They used this cult around the remains of their ancestors to stabilise their empire by commandeering the ancestors of conquered people and thereby exchanging the care of these remains for the loyalty of their relatives (Heaney 2023). In general, the deceased and mummified ancestors were still included as active and acting figures in social and political life (D’Altroy 2015; Kaulicke 2015). The Catholics, who had a tradition of venerating bones and other remains of martyrs and saints, used this cult of relics to spread their faith and thereby expand their power. The ideas surrounding bodily remains are by no means the same, but they are similar in the understanding that the remains have the potential to mediate between the living and the dead. While enabling cultural and religious mediations between Andean peoples and Christian missionaries, at the same time, the human remains, which could in both cultural contexts embody great political, social and religious significance, represented assets of conflict and competition. This point of conflict becomes clear in the precarious handling and even systematic destruction of ancestral remains by the oppressors.

Previous research has not only focused on the significance of the mummified ancestors and rulers of the Andean peoples, but also on how Europeans have dealt with them. Margit Kern, for example, shows in her concise article “Tote Körper — lebende Bilder” (2018) how the mummified Inca rulers were reframed and thereby “muted.” By systematically destroying them or exhibiting them as curiosities, the Spaniards deprived them of the performative power and thus the “ability to speak.” Similarly, Christopher Heaney argues in his essay “How to Make an Inca Mummy” (2018) that the preserved Inca bodies were profaned by the Europeans in the 16th century and re-categorised as scientific objects.

One aspect that appears to be present in the cases analysed, but which has not yet been examined in detail, is the relationship to the Catholic cult of relics that the Christian missionaries brought with them. While one body cult was being eradicated by any means necessary, another was introduced and celebrated. Building on research into the handling of ancestral remains in the Andes, the project will investigate the role played by the Christian cult of relics in the reinterpretation, remodelling and attempted destruction or replacement of these Andean ancestral remains. In doing so, it will also examine the extent to which the handling and understanding of Christian body relics themselves changed in the new cultural context.