RP1: West-Central Africa (Kingdom of Kongo)

Politics of Bones: Ancestral Remains and Christian Body Relics in Kongo Cultural Performance

Regional Project 1 (RP1) will revolve around epistemological and ontological meaning-making strategies in dealing with ancestral remains in the early modern Kingdom of Kongo and its surrounding polities.

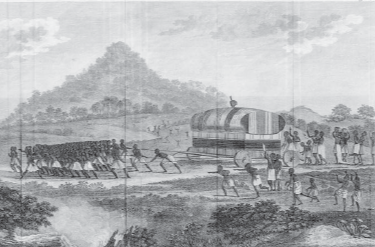

Previous research has highlighted the role of Minkisi cultural-religious assets in Kongo cosmology. For this study it will be particularly interesting, however, to highlight the role of Muzidi and Niombo that contained human body fragments or entire mummified bodies of deceased elders and chiefs. The Niombo shrouding technique, for example, produced larger-than-life entities, which were the centre of festive processions. While traces of these traditions have only survived from the late 18th century, the consideration of archaeological and linguistic findings will shed more light on the early modern practices of dealing with the dead. Furthermore, ancestral remains would often play a central part in succession processes, where they featured as meaningful elements of political legitimacy.

It will be of particular interest to interrogate the developments of earlier practices of life and death in the contact with an arriving Catholicism, which was deliberately embraced by King Nzinga a Nkuwu of Kongo (r. 1470—1509), leading to his baptism as João I in 1491 and the adoption of Christianity as a state religion by his son and successor Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga (r. 1509–1542). The development of Kongo Christianity as a continually evolving worldview was substantially based on the creative choices of the Kongo elite in creating new coherence between the novel Christian ideas and existing visual forms, religious thought and political concepts. This process had serious implications for the people of the lower Congo region, however, who were often forced by the new Christian clergy to destroy their cultural-religious assets, which had been central to pre-Christian ontological meaning-making processes. While there were white missionaries in the region, the larger part of the conversion practice had been conducted by a new Kongo clergy, which had received theological training in Portugal since the early 16th century.

The strategies for dealing with ancestral remains in the context of Kongo Christianity have changed through time. This process took place in a “space of correlation,” as Cécile Fromont has called the analytical tool which is applied to this study in favour of earlier terms like “syncretism” or “acculturation” to describe cross-cultural interactions, due to its advantage of attributing more individual agency to the actors and creators of artworks, performances and cultural-religious assets. In addition, while the earlier terms developed in postcolonial discourse and were generally understood to be set in what Mary Louise Pratt called “contact zones,” early modern contact between the kingdoms of the Lower Congo and the Portuguese Empire was initially characterised much more by curiosity and economical exchange than by foreign oppression. Applying “spaces of correlation” as an analytical tool allows for perspectives that focus on the aesthetic choices of the actors and creators. The methodological approach is therefore both art historical and anthropological. By understanding religion as an essentially cultural phenomenon, African philosophy provides the indispensable base from which to try to shed light on the manifold cultural-religious roles related to human body fragments in cultural-religious assets of the Lower Congo region.

More recent research on the art historical aspects of visual form and religious thought has been carried out by Cécile Fromont, based in many cases on the ground-breaking study of Robert Farris Thompson. And the analysis of the political history of the region is largely based on the findings of John K. Thornton and Wyatt MacGaffey. This project aims to provide further perspective on the history of the region and Kongo Christianity as a coherent worldview by highlighting the strategies surrounding human remains as a central “space of correlation” in this early modern contact.